Thanks to my patrons for supporting this article!

Strategy games, in some ways, are all about limitations. You have limited resources to spend on units and structures at any given time, limited time to react to enemy attacks and tactics, limited attention and reaction speed to manage as you try to eke the most out of your limited supply of units, each with its own constrained functionality.

There is a huge element of skill in strategy games which revolves around mitigating your limitations: ramping up your economy quickly to build (or rebuild) as large an army as quickly as you can (or on striking with an unexpectedly quick army), maximizing your efficiency in combat so that each unit does as much damage as possible to the enemy, paying for itself multiple times and forcing your enemy into a resource deficit so they need to spend resources on rebuilding while you spend them on getting farther ahead. Pure, brual efficiency is a core watchword of RTS, and generally centers around dealing as much damage as possible as quickly and with the least damage and cost to yourself that you can manage.

This is fine, this is well and good, and this is how the game (no matter if it’s StarCraft or Age of Empires or Command and Conquer or a hypothetical My Little Pony RTS) is played.

But as the genre has matured, designers have experimented with different types of efficiency. Brute forcing DPS can only get you so far, you see. We’ll talk about that, it’s important to the conversation.

So, bottom line, what is this article about? What is the point I’m trying to articulate? First, it’s that strategy games are best when they include roughly 3 or 4 somewhat independent systems for players to pursue success. And second, that at least some of these systems should provide temporary or recoverable advantages for a player over another. And how giving units ammunition can help with all this.

Binary Is Bad: Gradations Keep Things Interesting

Fundamentally, I see strategy game design as a delicate balance between 3 primary and somewhat oppositional driving mindets. First, quality RTS design dictates that every system in the game should provide players increasing incremental benefits for skillful handling: the more attention and control you execute on a system, the more you should benefit from it, even though there may be decreasing returns from doing so. Some examples of this include mineral line management in StarCraft 2 including knowing when to expand and some of the little tricks you can pull to eke a slightly higher income out of mineral mining in the early game, Marine splitting to counter Banelings, or strategically selling structures in C&C games. Most combat ‘micro’ falls into this category, though economics management is important here as well.

Secondly, strategy games are most interesting when they present multiple success and failure states for any given action. If combat encounters are prone to ending with one player’s force entirely decimated while the other player has a substantial army left, the game will mostly likely feature many situations where matches are decided after a very few encounters: this is common in StarCraft 2 matches, where a single successful attack can and often does irrevocably decide the match. Tooth and Tail features an even more binary system, leaving a player almost without options or recourse if their opponent gets solidly ahead of them in production or income, especially in the early game.

Creating situations where combat is able to resolve in a partially successful or partially unsuccesful state, allowing players to avoid total and catastrophic failure across the broadest subset of combat and harass encounters, allows the game to continue and a player who might have been temporarily set at a disadvantage through sloppy play or a momentary inattention to redeem themselves, while still putting the player with the better performance at the advantage. For instance, in the Company of Heroes and Dawn of War games, being able to retreat squads back to your base allows you to retain combat ability despite the loss of whatever point of ground those units were striving to hold or gain.

Or in WarCraft 3, where unit health pools tend to be large enough to allow constant poke-and-prodding while players jocky for the stun or body block that allows them to whittle away their opponent’s army. Or, to also use WarCraft 3 as an example, where each faction has options regarding base defense: Burrows for Orcs, Ancients for Night Elves, that allow a player to minimize their losses while their army runs or Town Portals back to defend their buildings and units.

There can be tremendous nuance in these systems: in Relic’s retreat mechanic, knowing where and when to retreat, as well as knowing the fleeing squad’s path back to base is critical: it is possible for a player line up a high damage squads along retreat paths to snipe fleeing units, making the system still one where skill is involved.

Taking A Look At Skill

Why does this matter? Clearly, in strategy games, the player who is better should win, so why prolong the agony of the other player’s defeat? Why give the worse player more chances to accidentally (or via dumb luck) defeat their superior opponent? This comes down to the nature, and the fun, of strategy games. It comes down to creating interesting competitive experieinces for people, and participating in those experiences yourself.

Fundamentally and frankly, I’m basing this assessment on overall game feel and what I see as an effort to keep matches fun and interesting for as long as possible and across the widest possible subset of matches; I see specific mechanical paths towards making that a reality. Please understand that I am advocating for a personal preference in game design and that I’m pushing for a slightly different definition of ‘skillful play’ and even of ‘winning’ than you might see in most strategy games. What I’m looking to do is advocate for game designs that allow players to feel like they’re still able to act and participate in the game even when they’re losing. I am advocating for empowering players, and trying to acknowledge the drawbacks of my recommendations as I put them forward.

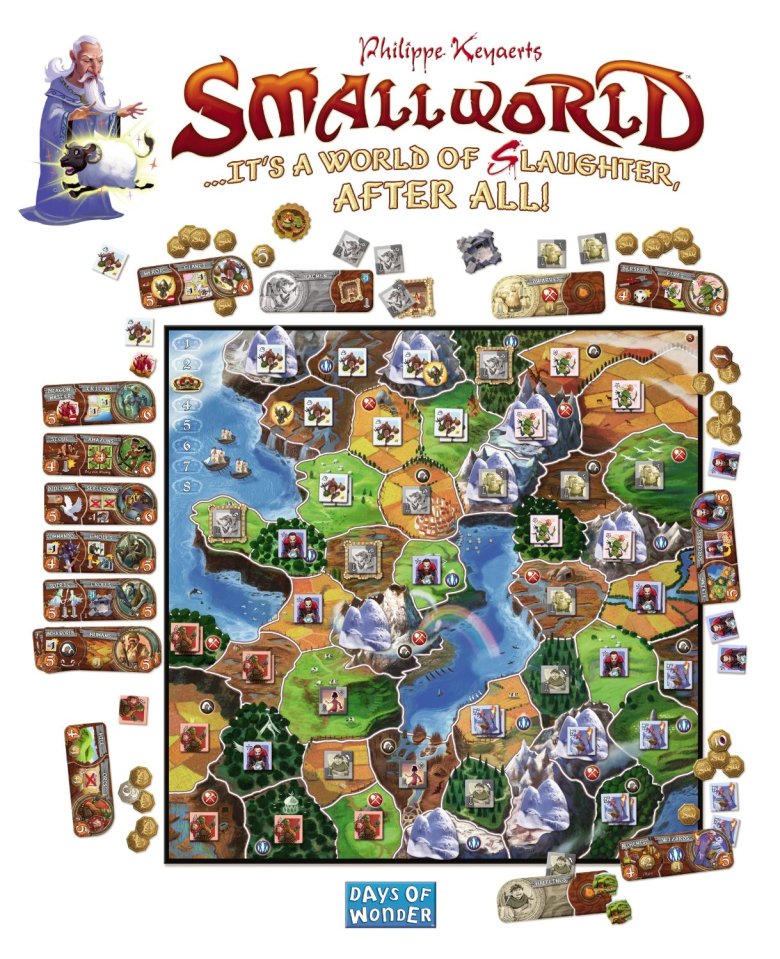

In strategy games, as in all competitive games, the player with the better strategy and execution deserves to win. But consider a game like SmallWorld, or like tabletop Warhammer 40,000, where the winner is almost always determined by the end state of the game upon its end condition being met, or in Dawn of War with its Relic win, or in Age of Empires where one can achieve an economic and defensive victory via a Wonder, allows win states at least somewhat independent of either player’s overall ability to wage war.

Skill-based victory is still skill-based victory. There will always be situations in skill-based competitive games where a crushing victory happens, and that’s fine and good. What I’m interested in is strategy games which force the better player to have more consistency in establishing dominance, or in having them win while still allowing the losing player access to all or most of their ability to act on the game. What I am also interested in is systems which encourage players to master and demonstrate skill along multiple avenues in order to achieve success.

Multiple Avenues For Success

It is my contention that competitive games are most interesting when all players feel like they have some option to continue and succeed for as long as possible. Clearly, there will come a moment when success, and more importantly the feeling of being able to succeed, will be lost for one player or team, but that moment can and should be pushed back as much as possible. When a player feels they are unable to act on the game in meaningful ways, when it feels like they have no options or control, they are frustrated.

And just what does this have to do with ammo, mana, morale, and other similar systems in strategy games? I’m getting to that. Bear with me.

Above, I have tried to lay out my position that a state of homeostasis or equilibrium (analogous to the midgame phase of most RTS) creates the most interesting game state for both players, and that tipping the game from this state towards a win should require, in most cases, repeated successes by a dominant player in order to insure a win. Further, this should be facilitated via systems like:

- Multiple systems that drive player success, each being at least partially independent from one another. This allows players to still go for a win if their opponent hampers their effectiveness in another area. An easy example is in StarCraft 2 early to mid-game, when players can choose a combination of economic expansion, army size, harassment options, or tech to attempt to overpower their opponent.

- Win conditions that are divorced from a player’s ability to play the game. For instance, in StarCraft you win by removing your opponent’s ability to fight back, while in Dawn of War 2 you win by reducing your opponent’s Victory Point total to 0 by holding more VPs than your opponent for longer.

- Creating systems where players can recoup or reatreat from a loss, or where combat outcomes tend to be less binary. One example is the Retreat mechanic found in the Dawn of War and Company of Heroes games.

So here’s where we get to efficiency. The fewer vectors for success there are, the more success is driven by efficiency along those vectors. In StarCraft 2, for example: the core resources of Minerals and Vespene are the primary mechanism for expanding the player’s options and acting on the game state, and expanding a player’s income with both of these is vitally important. But the number and position of each unit factory type also affects a player’s ability to produce units, and having too many or too few of a given factory type can itself cause problems. Likewise, while upgrades in StarCraft can sometimes be subtle, sometimes having additional armor or damage can tip a type in your favor: overall, managing all of these things provides each player with a number of interesting choices for how to develop and implement their strategy… in ways that often are completely undone by players’ (especially those in Platinum league and below) to deathball their massive armies around, where victory often devolves into who can kill the other player’s army more often and rebuild theirs more often.

So all of those interesting choices, except at the higher levels of play, can definitely be bypassed or subsumed under the weight of income and DPS. Obviously, this is a bit reductive: abilities, positioning, and other tactical and strategic considerations (force field, observers, roots, psy storm, etc) can and do come into play.

Breaking it down, StarCraft 2 has a lot of factors in play, many of which are at least partially avoidable or ignorable, until high levels of play. I mean, it’s a pretty flexible and robust system. There’s a reason it’s so popular.

Let’s contrast this with Tooth and Tail, though. In Tooth and Tail, there is only one resource: food. And it’s used to build structures, build units, build farms (economy) and take new bases/territory. So ultimately, everything in Tooth and Tail comes down to food. And that’s the point of the game. It’s incredibly focused, and I think that’s praiseworthy. But in multiplayer, it can be merciless. Once things start going badly for you in Tooth and Tail, especially in that pernicious early game before you’ve expanded, losing, well, anything can put you into the kind of tailspin that happens in Zerg v Zerg matches in StarCraft 2: that is, you’ll never be able to catch up economically. Economy growth curves make it increasingly statistically likely that food ‘wasted’ on units you have to rebuild will allow your opponent to get that much farther ahead, have more resources to spend on units, and so on rolls the snowball.

Combat in Tooth and Tail is much more linear than StarCraft 2, since you basically only have the ‘levers’ of combat skill, unit choice/positioning (there is an interesting element here where you’re able to choose between lower level and higher level/more powerful units, but that strongly correlates to income), and income to pull, and they’ve been somewhat dulled by passing all orders through the imprecise sieve of your Leader unit.

To further belabor the point, Company of Heroes 2 gives players a good variety of levers to pull: Manpower is largely fixed income, which inflates or decreases based on how many extant units you have. Fuel is scarce and punishes poor play with vehicle units. Munitions start out scarce but become plentiful in the mid-to-late game, where armies are larger and dealing wide damage with Napalm is a little easier to come back from. Add to this a really dynamic infantry combat system with cover, morale and the suppression system, smoke and grenades and indirect fire weapons. This expands to include light vehicles, which interact differently with indirect fire and MG weapons and regular infantry, then expands again with heavier vehicles and AT guns, and expands again in the late game with super-heavy tanks. Each phase of the game increases the number and nuance of interactions, while expanding Munitions income allows more consistent use of game-changing abilities.

So, in Company of Heroes 2 you have those 3 resources (4, really, if you count VPs as a resource), each with its own purpose, that players can spend in various ways, then there’s the interlocking unit dynamics that has little, but some, leeway built into it – like how MGs can provide light anti-tank in the early game if a player is slow to get out true AT solutions (obviously unit choice is a big component of Company of Heroes games). There’s territory control, which of course influences income to a degree, but manpower (unit counts) are offset somewhat by skillful use of Munitions (special abilities) and fuel (many tanks mow down infantry). It’s not a perfect system, but I see a lot of promise in it.

So, ah, ok. Let’s boil all of those examples back down to a concise statement.

Give players multiple avenues for success. Have those avenues bottlenecked in some way, but somewhat independent of each other, as well. Few avenues for success means less strategic diversity, which means the game will get boring.

…God, this is going to require a follow-up piece where I try to lay out the reasons I think 3-5 main actionable paths to pursue is the best number. Let’s put a pin in that idea for now and finally start talking about ammo systems.

Ammo, Mana, and the Cost of Doing Business

All right, we’ve had our fun talking about the first part of this topic: the idea of multiple paths or vectors, or levers that players can pull to drive success, and how that can help establish equilibrium or homeostasis. Or at least, why I think such a goal is a positive thing.

Now let’s talk about ways to temporarily upset that equilibrium.

As a player, you don’t want to temporarily upset the equilibrium. You want to grab your opponent by the throat and grind them into the dust until there’s nothing left but pillage and lamentations. Which is all well and good, that’s what we’re all here for. I’m just all about making you, the player, work for it and give a little more effort than executing one decent six-pool or cannon rush. Because I’m also thinking about you, as the player, getting grabbed by the throat and ground into the dust until there’s nothing left but lamentations. About the situations where losses feel unfair and wins seem inevitable. About ways to give both players or teams an enjoyable experience as often as possible while still having the more skilled team/player take the win in the end.

So, in general, I’m in favor of things that offset your opponent’s efforts to wage war, temporarily. Something you can do to put your opponent on the back foot, that will require them to regroup and cede control to you, but which can later be rectified and bring them back to battle without that Tooth and Tail, Zerg versus Zerg style snowball towards irrelevance in the battle.

Relic’s games, as brutal as they are, are filled with such systems. Vehicle damage states, like busted engines, are status effects which limit the operating power of those large, game-altering units in ways that let the player bring them back to bear in the future. Vehicles can be crippled (or stolen! I hope to get into object permanence in RTS sometime soon), and bringing them back to full fighting fury is a time and resource commitment, but far less so than replacing one outright. It’s a temporal, temporary advantage.

Ammo systems work similarly. In games like Earth 2150, Wargame AirLand Battle, et cetera, there exist systems that, if disrupted, leave a portion of your army unable to respond. It’s a way to fight a larger and better-equipped army, a way to take enemies out of the fight to deal with later, a method for stalling assaults and creating stalemates of victory marches.

In systems where units use ammunition, the typical implementation is some combination of a mobile unit or stationary structure which provides nearby allies with a personal stockpile of a resource which is depleted every time that unit attacks. Without continual resupply, one’s army eventually will run out of ammo, and become unable to attack. Wargame and its sister Steel Division take this a step further, with units also requiring fuel to be able to continue to move around the map.

These systems, and the others I will discuss, are ways to temporarily throw a monkey wrench into the larger calculus of efficiency, and allow space for a player who might have fallen behind to temporarily reset the scales of balance in their favor.

Blizzard, of course, realized this sort of thing as well as its downsides, and relegated this idea solely to spellcaster units, such that a portion of your army becomes useless when out of its ‘ammo’ – and I think they’ve actually backed off of that a bit, with many Mana-based units having a way to recoup said ‘ammo’ or to not be completely useless without it.

Because, of course, without ammo, units can’t fire their weapons, which means in effect they become useless. Not an ideal situation if you are already behind. And, yeah, kind of frustrating even if you’re ahead.

One neat thing about ammo systems though is that they’re usually not immediate: unlike an EMP or High Templar Feedback, there’s a bit of a delayed impact to cutting off an ammunition supply. Ammo or Mana is a resource that isn’t binary, and is depleted over time. So the player who’s lost their supply of ammunition has a chance to correct the situation before it bites them in the butt. Remember what I said earlier about binary situations being bad and gradations being good? Well here it is. The feeling of panic you get when you know your army’s going to start losing effectiveness quick if you can’t reestablish your stockpiles soon, that’s much better than the abject frustration of being subject to a root effect and completely unable to respond while your army is obliterated by high-octane area damage.

Steel Division and Wargame attempt to deal with the binary nature of their ammo and fuel systems via the sheer quantity of units that the player is fielding, offset with variable ammo costs based on weapon type. Artillery shells? That’ll empty out an ammo supply vehicle pretty quickly. Infantry or tank-mounted machine gun bullets? A different story altogether. This encourages unit mixing and a combination of retreating to a FOB and careful management and hiding of valuable ammo supply weapons, which are the lynchpin of your ability to operate out on the map.

Also, having a mix of ammo-dependent and ammo-independent units or actions (as Blizzard does with spellcasters) is a good way to offset the impact of this, though I feel that StarCraft in particular is too conservative with ammo – WarCraft 3 was a much stronger approach, given the power of hero and spellcaster units, and the depth of interactions involving mana usage (think of anti-spellcaster tools such as mana drain and feedback). The sub-economy of mana manipulation is another one of those multiple avenues for success we were talking about earlier – see how it’s all tying together?

Doing Nothing: Some Problems With Ammo Systems

Efficiency, as I said, is one of the core watchwords of RTS design. RTS players will always try to find the most efficient ways to gain an advantage over their opponent (and having multiple semi-independent game systems is one key way to make this aspect of the game more multi-faceted and interesting). And the problem with any sort of ammunition system is to make it important enough for players to pay attention while limiting its overall impact so that it doesn’t override other important game systems.

And, yeah, that’s the problem with most game systems, so it’s not really a surprise. I just feel like it bears mentioning here since I’m effectively advocating for the increased use of ammo systems in strategy games.

Practically, there are of course a number of issues with ammo systems that circumvent the traditional focus on pure DPS efficiency, which I touched on above very briefly. One of the big ones is that ammunition systems that have a unit-based or otherwise killable munitions delivery system are prone to DPS-related upsetting. That is, the player with the most DPS delivery power is going to have a better chance of knocking out ammo delivery systems anyway. This is the Gordian Knot of DPS that’s proven very difficult to slice in strategy game design: damage output covers a multitude of woes, and often the alternatives are worse, not better.

Ammo systems can also feel damned unfair, especially if they’re binary or widely implemented across the army. Just as wide-area stuns and CC can feel awful for the impacted player, Wargame-style munitions can suck when your entire war machine grinds to a halt because of a handful of dead logistics units. Which, of course, is why I think it’s smarter to use a system like you see in Earth 2150, where different types of weapon behave according to different rules, like laser weapons need to recharge but don’t need restocking, or plasma weapons overheat over time, damaging the carrying unit unless it ceases fire for a while. That sort of thing.

Wrapping Up

I started by trying to make the case against binary outcomes in real-time strategy game encounters: they’re going to happen, of course, but my point is that systems can be tweaked and implemented that cause them to be more of an outlier. That games feel best when players perceive that they have meaningful ways to interact with the game they’re playing (especially in a competitive game) and that RTS can encourage such equilibrium or homeostasis by, among other things, providing multiple semi-independent ways to succeed.

I tried to build on that foundation by positing that ammunition systems work really well as methods to temporarily offset my desired equilibrium state – losing a supply line provides a cutoff to DPS-based interactions, which shifts the focus from pure DPS to preserving one’s ability to continue to support their army’s continued operation. Tied with win conditions that are themselves partially independent of a player’s ability to fight, that is: win conditions not reliant upon stripping your enemy’s ability to fight back, such systems provide more vectors for interaction and decreases the amount that any individual vector can lead to a decisive win.

The same goes for ‘power’ mechanics like we see in Supreme Commander or Command and Conquer, of course, and early drafts of this article tried to shoehorn that in as well. I decided – for brevity, you see – to exclude talking about power plants or suppression (another temporary offset that I favor, though I think ammo systems are overall better) here. Maybe there’s another 4000+ words on that floating around, waiting to be unleashed.

I hope that, at least, I’ve given you something to think about. This piece is more a look into my personal philosophy on strategy game design than a substantive case or analysis of existing mechanical systems, and as such I think the most I can hope for is to inspire some thinking and possibly conversation about ammo systems and competitive gameplay dynamics.

Thank you for your time, and as always: see you on the battlefield!

A Note On This Article And My Writing In General

In my writing, I advocate for what I see as strategy game systems designed to empower players and to create gameplay experiences that are fun, meaningful, deep, and fair. I am an avid and passionate strategy game player, though not a particularly skilled one, and most of my observations are drawn from my own experiences and preferences.

Also, I’d like to apologize to Pocketwatch Games up front. I think Tooth and Tail is a great game, but its design really lends itself to the particular issues this post raises, so I use it as a somewhat negative example several times in this article.

First, let me say that I really enjoy your blog and I’m very glad I found it.

I generally agree that games are better when they are less swingy.

But I think players bear some responsibility here.

In my understanding, strategy games are very much about the competing drives of greed and caution. (Starcraft) Do I take another expansion, or hold off? Do I make high-DPS marines that shoot up, or more durable Marauders? Do I go harass or keep those units home Just In Case?

What is a nearly guaranteed way to make the game swingy? Make it swingy by going all-in somehow. Turtle to void rays. “Rush fuel.” These are very popular strategies,

I don’t mean to inject morality here—players can play however they want—but the prevailing style means that games can often be less swingy in design than they might appear judging from how they are played.

One of the things I’ve started to value in my play is the idea of stability. How can I increase the reaction time I’m allowed before things go completely to hell?

Thinking this way has forced me to bend my mind a little. For instance:Zerg. How does one play a race like that safely? By attacking, it turns out—with units that I don’t mind losing.

I get the impression from the communities I frequent that I am something of an anomaly in how much effort I put into this idea. It is in some ways a very unrewarding style, because it doesn’t provide short-term rewards. So I completely understand why people don’t do it. But I think that idea that players make things swingy deserves mention in the conversation.

LikeLike