Last week, I wrote a piece in which I attempted to define what an RTS is. Working from that definition and some of the points made in that article, I would like to discuss what I consider to be the benefits of playing RTS games in particular. As I wrote in last weeks’ article: “RTS, to me at least, are more than idle ways to pass the time, ways to blow off steam, or a means of escapism; they’re playgorunds for exercising the mind, and they do so in ways that I contest few other genres can. Among other things, playing RTS can strengthen skills like self-analysis, critical thinking, planning and decision making, and reinforce a proactive, positive approach to life and adversity.”

And that is exactly what I want to examine and explore in this article, with a hefty dose of what I consider to be the primary sources of fun and challenge, to boot.

Self Analysis

One of the primary things you learn when beginning to play RTS is that they are hard. So difficult are they, in fact, that in virtually every case new players turn to watching gameplay analysis of better players, reading how-tos and strategy guides and memorizing popular build orders to get ahead. It’s very difficult for the average player to craft winning strategies without the support of a larger community contributing to a common pool of knowledge of how to play the game (this is often called the game’s ‘meta’).

One paragon tool for improvement is the player’s own gameplay, recorded in most major RTS in the form of replays of past matches they’ve played. Many RTS, from Grey Goo to Company of Heroes 2, to StarCraft 2 and Supreme Commander, have options to automatically save all of a players’ past games into a replays repository for review upon demand. Supreme Commander innovated with GPGNet, and Blizzard with Battle.net, simple ways to share replays with others, and services like gamereplays.org exist as places for players to seek advice from game communities via their replays on how to improve at any given title.

In the StarCraft 2 community in particular (as well as in the Supreme Commander community during its heyday) it is very common to see players spend almost as much time going over their replays, both of victories and defeats, as they do actually playing; they want to see what both they and their opponent did well and did poorly. Defeats, the common wisdom goes, are often more valuable learning tools than victories. What did my opponent do that I can incorporate or improve upon? Where did the game turn around, and why? What choices could I have made differently, where were the weaknesses in my strategy? YouTuber and eSports personality Day[9] rose to prominence for a friendly, positive approach to teaching newer players these sorts of thought patterns: what did this pro do well? What did they do poorly? How can I use this unit in creative ways, or how can I cope with this unorthodox situation?

What this all exemplifies and reinforces in the RTS player is critical self-analysis, a skill most all of us could use polishing up on. Both in RTS and in life, it is an invaluable skill to be able to review one’s past performance clinically, not to agonize over past mistakes but to learn real lessons on how to avoid future mistakes. It has been said that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” and RTS make this baldly apparent. The same mistakes result in the same losses under the same scenarios. There’s no such thing as ‘good enough’ – there’s always going to be someone better out there.

The journey, as it turns out, is the reward: learning from ones’ mistakes, being able to view a defeat as a learning opportunity instead of a setback, a chance to grow instead of an ego-crushing validation of one’s own negative thoughts about themselves. I’ve seen RTS players advocate eschewing a focus on one’s win-loss ratio or win percentage, intentionally ‘throwing’ tens or dozens of matches so there’s nowhere to go but up. Ladder anxiety can be combated by the right mindset, one where the player is constantly seeking to learn, to improve, and to enjoy the competition. Sure, losing sucks, but the good players will incorporate the lessons from their losses to turn future encounters into wins.

In RTS and in life, if you’re not learning, you’re losing, and even if you’ve had a defeat or setback, as long as you’ve learned from it you haven’t lost. RTS is an excellent arena for this, as are most competitive games. What makes RTS special? Well, in addition to promoting a positive attitude towards learning from losses (which organized sports should also teach, as well as MOBAs, FPS and most other competitive games). Let’s take a look at some more skills and behaviors that RTS can help players train/reinforce.

Critical Thinking and Pressure

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: RTS are difficult! They ask more of their players than virtually any other genre of game, with the possible exception of the fighting game genre. Building bases, upgrading units, braving the fog of war to see what your opponent’s up to, microing units, macro-ing, balancing and increasing your resources, expanding, moving, coordinating attacks and defenses. And, most importantly, they have you do all of these things with limited resources. In most RTS, there will be 1, 2 or more concrete resources to acquire, manage, and spend as well as implicit resources like time, attention, and knowledge of what one’s enemy is up to.

RTS intentionally put pressure on their players to make effective decisions quickly and with limited information. This, ultimately, is a training ground for critical thinking. RTS players are intended to have a broad knowledge of the options available to them and their opponents, including but not limited to the functions and rough timings for enemy units and strategies, the implications of play for any given terrain features in use on the particular play area (for instance in StarCraft 2, Zerg tend to fare better in open areas away from cliffs or chokepoints, while Protoss tend to prefer to fight Zerg in chokes but Terrans in more open areas) or a build order that gets a player to a certain game state as efficiently as possible.

To win, players must spend both their in-game resources and their implicit resources wisely, and make accurate, quick decisions based on incomplete or potentially inaccurate evidence. Where is your opponent’s army? Do they have a strike force sneaking around the back of your base/force to snipe off important investments? How does your opponent’s income stack up against yours? How does their production? What’s the best path forward, considering both your game state and that of your opponent? Are they building a superweapon?

Planetary Annihilation does something quite interesting in this space, with its multi-planet systems, spherical planet shapes, and multiple information layers per planet (ground and orbital, each requiring their own detection systems) requiring the player to be very, very proactive in seeking information, as well as making such information indespensibly important. Have they expanded to the Metal planet? Are they building an Annihilaser? Are they loading that moon up with Halleys? Are there nukes being built? How can I get my forces onto this fortressed up world?

To win, players must think critically both in the short term and long term. In the short term, misplaced armies, mismanaged units, and mistimed abilities (assuming the game contains active abilities of some sort, either on units or in the form of global effects like superweapons) can cost a player a match outright. In the long term, inefficient economy growth, passivity, and misreading of an opponent’s strategy can leave a player in an unwinnable position. And players are unable to do everything they might want, all at once. this is core to the RTS genre, and the reason for build orders, army compositions and the like. Players tend to be required to focus on a relatively small number of things at once, and the ability to evaluate ones’ options and choose an effective way forward in a matter of moments is an invaluable skill to train, both in the artificial arena of an RTS game, and in the actual arenas of life.

Few general skills are as valuable and transferable as the ability to make accurate decisions decisively, under pressure, and with limited information. It’s important in the boardroom, when deciding where to go eat with a significant other, in evaluating the wisdom of a potential impulse buy, et cetera. Not to say, of course, that RTS will assuredly improve a person’s ability to make decisions, but in general, practice in being decisive and executing on a plan is only good for the practicioner.

Executing on a Plan

Speaking of pressure, this tends to be a key compontent of RTS games. Pressure provides a large portion of the challenge and benefit of making such games real-time. Unlike in virtually all 4X or Grand Strategy, players aren’t in control of the pacing of the game, and are (as mentioned above) asked to do quite a lot of things at once, while meaningfully planning and executing on a strategy that can take upwards of 20 minutes to put together.

Now, RPGs and 4X games tend to span a continuous narrative across tens of hours of play and potentially months of objective time. These games can train long-term decision making and planning in ways RTS, which are session based, cannot. However, it’s seldom that players are asked to create a plan and asked to build and protect a complex system to execute it within the course of 30 or so minutes. To do this takes intense concentration, mental endurance, and adaptability. RTS is virtually unique in its blending of short term decision making and intermediate term decision making in the video gaming space, with only some board games really capturing this requirement within discrete sessions or matches: most shooters tend not to have meaningful personal or even team progression across the breadth of their matches, and even MOBAs, which tend to last significantly longer than RTS matches, have downtime, a decreased burden of overall awareness of the game state (since each player is only one fifth of the effort being put into winning the match) and, arguably if not definitively, have fewer types of progression that must be monitored and planned to effectively advance into the latter stages of play.

So what does this mean and what is its significance? Well, ultimately, it means “RTS are hard!” I told you I’d say it again. practically, RTS require constant high level mental engagement from players, exercising planning and concentration in ways that are not seen in FPS, RPG, MOBA etc, broadly speaking. As mentioned before, they challenge both short term and long term planning, though some RTS tend to favor one or the other of these more.

Looking at StarCraft or any -Annihilation or -Commander, the number of things the player has to juggle and think about can increase exponentially across the course of a match, with inefficiency and inattention to detail punishable by ignominous defeat. Look at progamers like Idra, who was known for incredible efficiency in play, with very low resources ‘wasted’ up to several minutes into a game, indicating he had hid build orders planned and executed down, virtually, to the second. That sort of concentration, adaptability and planning is useful (again) in the workplace, business and more.

The Challenge and The Fun

To me, these challenges are part of the fun. It’s immensely satisfying to outwit, outplan, and outmaneuver another human person, especially if you can be reasonably assured that the other human person is roughly about as good at the game as you are (there’s a topic for future articles, matchmaking!) RTS gamers tend to get a rush from, well, feeling superior. The planning isn’t enough, the multitaksing and micro themselves aren’t enough, though there is a high degree of satisfaction in artistic or novel play and execution (there’s a reason people love watching StarCarft 2, after all!). Even the winning itself, while it provides a rush, aren’t enough.

I think, anecdotally of course, and speaking from personal experience, the journey is the destination (as I said before). Challenging oneself to improve in this aspect of play, to face up against a strategy that previously crushed you utterly, to be the sole author of one’s victory, match after match, and challenge after challenge. I’m using high-handed language, sure. And most of this article is bloviation about life skills that can be honed or practiced by playing a particular type of game.

RTS push you to your mental limits, and taunt you with the promise of improvement, just around the corner. They tempt you to spend those hours analyzing, reviewing, learning and improving to increase a score that is ultimately meaningless in the real world (unless you end up winning money in a tournament). But behind that is a mindset of progress, of overcoming adversity, of sticking it out defeat after defeat until victory is achieved, and I think that should be celebrated.

Thanks for your time.

Hello. I want to say you have a great talent to observe things, but the reasoning is poor and ability to come to a conclusion is zero. To put it laconicaly, the very things you claim RTS nourish, are the very thins you lack. Still better then mr. Day9 who goes into three pages long pseudo-scientific conundrum so he do not have to accept that the “negative things that are happening somewhere in our body when we play Starcraft II” is Starcraft II itself. The conclusion is: Starcraft II is an enjoyable thing that causes anxiety. Would you believe a guy like that develops a multimilion game? Anyway. Onto the topic.

Self Analysis. The premise of this article is correct. The text of this article proves the premise of RTS is wrong.

“One of the primary things you learn when beginning to play RTS is that they are hard. So difficult are they, in fact, that in virtually every case new players turn to watching gameplay analysis of better players, reading how-tos and strategy guides and memorizing popular build orders to get ahead. It’s very difficult for the average player to craft winning strategies without the support of a larger community contributing to a common pool of knowledge of how to play the game (this is often called the game’s ‘meta’).”

This paragraph alone rebukes the whole premise that RTS are about thinking and coming up with your own plan, strategy and tactic. Not only is the best and most effective way of improving simply coping others, coming up with your own plan,strategy and tactic is “very difficult for the average player”. Morevoer if a strategy can be crafted outside of a match, it means what happens in an actual match is less important then build orders. Which invalidates about half of this post. Or maybe the whole post.

“One paragon tool for improvement is the player’s own gameplay, recorded in most major RTS in the form of replays of past matches they’ve played. Many RTS, from Grey Goo to Company of Heroes 2, to StarCraft 2 and Supreme Commander, have options to automatically save all of a players’ past games into a replays repository for review upon demand. Supreme Commander innovated with GPGNet, and Blizzard with Battle.net, simple ways to share replays with others, and services like gamereplays.org exist as places for players to seek advice from game communities via their replays on how to improve at any given title.”

Why do you need replay in order to improve? Because sucess requires knowledge of build order. The more build order I know, the more matches I am able to win. Therefore I need to watch the replay to know what kind of build order the oponent went for so I can learn how to counter it and win.

“In the StarCraft 2 community in particular (as well as in the Supreme Commander community during its heyday) it is very common to see players spend almost as much time going over their replays, both of victories and defeats, as they do actually playing; they want to see what both they and their opponent did well and did poorly. Defeats, the common wisdom goes, are often more valuable learning tools than victories. What did my opponent do that I can incorporate or improve upon? Where did the game turn around, and why? What choices could I have made differently, where were the weaknesses in my strategy? YouTuber and eSports personality Day[9] rose to prominence for a friendly, positive approach to teaching newer players these sorts of thought patterns: what did this pro do well? What did they do poorly? How can I use this unit in creative ways, or how can I cope with this unorthodox situation?”

Why do I need to improve? Why would people spend almost as much time going over replays? Because RTS is about improving. Improving represent ability to score higher score or win more matches. Therefore RTS is about winning more matches. Not about playing matches, but winning matches. That is why players eschew 50% of game time (The point of the game.) for an elusive chance of higher win ration. (Which never going to materialize, because 50-50.) In other words, eschew low pleasure for middle pleasure in order to gain high pleasure.

“What this all exemplifies and reinforces in the RTS player is critical self-analysis, a skill most all of us could use polishing up on. Both in RTS and in life, it is an invaluable skill to be able to review one’s past performance clinically, not to agonize over past mistakes but to learn real lessons on how to avoid future mistakes. It has been said that “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” and RTS make this baldly apparent. The same mistakes result in the same losses under the same scenarios. There’s no such thing as ‘good enough’ – there’s always going to be someone better out there.”

Yeah, but that is not the nature of RTS, that is nature of contest. Contest itself does nothing to foster self-analysis. It is your decision to win more, lose less that drives you to self-analyse a situation. It is your own decision. RTS is simply a form of contest.

“The journey, as it turns out, is the reward: learning from ones’ mistakes, being able to view a defeat as a learning opportunity instead of a setback, a chance to grow instead of an ego-crushing validation of one’s own negative thoughts about themselves. I’ve seen RTS players advocate eschewing a focus on one’s win-loss ratio or win percentage, intentionally ‘throwing’ tens or dozens of matches so there’s nowhere to go but up. Ladder anxiety can be combated by the right mindset, one where the player is constantly seeking to learn, to improve, and to enjoy the competition. Sure, losing sucks, but the good players will incorporate the lessons from their losses to turn future encounters into wins.”

Now we are geting to some kind of zen psylosophy. “Enjoy what you do.” The problem is, in that case, the doing is not enjoyable. If it was, then you would “Do what you enjoy.” This kind of mindset is employed by people who want to do something uncomfortable. Something they want to overcome. Does that mean RTS is uncomfortable and something to overcome? Pretty much. If you talk about focus on victory, then it means victory is the most enjoyable part of a match. So the match itself is not enjoyable. To the point of players ‘throwing’ tens or dozens of matches so the only thing they can experience is joy of victory. That you decided to talk about ladder anxiety is interesting and fitting. Fear of loss is greater then joy of victory. Joy of gameplay cannot outwieghts it. So victory is the only thing that matter. Which leads into RTS is about improving. Because improving is about winnig more matches. Learn to love what you have to do is great, but why would anybody do it if they do not have to.

“In RTS and in life, if you’re not learning, you’re losing, and even if you’ve had a defeat or setback, as long as you’ve learned from it you haven’t lost. RTS is an excellent arena for this, as are most competitive games. What makes RTS special? Well, in addition to promoting a positive attitude towards learning from losses (which organized sports should also teach, as well as MOBAs, FPS and most other competitive games). Let’s take a look at some more skills and behaviors that RTS can help players train/reinforce.”

RTS ceased to be a game, I.E enjoyable way to spend past time and become something else. Comparison to life is entirely fitting. Just as humans want to escape the harsh reality of life by watching movies, reading books and playing games, so do want to RTS players escape the harsh reality of RTS by claiming it is about improvement, learning and positive attitude towards loses. Or maybe it is. The problem is that outside of 25% of RTS players, noone can understand it. It is like hack and slash. It is great, untill you realize you beat monsters to beat monsters. It is nothing to nothing. Unless you like the activity. RTS is the same. Improve so you can improve. Comparable meaningless. Why would I do it. Insted of playing RTS, I can go to school and earn a degree. It is the same thing. Except it means something. Now, playing LoL is of course equaly meanigless, the difference is, LoL brings a good feeling of fun and joy. RTS brings sweat and stress and sorrow. Call it competive, inteligent, hard core, hard, it does not matter.

This is why RTS do not work. Because people are more interested in having fun with their families, friends and strangers, then they are in going from work/school to work/school and dubious honour of being a grandmaster. Dirty casuals. Call them what you want, why would they get more of stress and sweat and sorrow? They have enought of that in their lifes already. Why would they get more of the bad stuff then they already have?They are not drug addicts. Well, the majority at least

LikeLiked by 1 person

Where to even begin on this?

“Self Analysis. The premise of this article is correct. The text of this article proves the premise of RTS is wrong.”

This assertion is just baseless. What you wrote after goes no further to demonstrating it is true.

“Morevoer if a strategy can be crafted outside of a match, it means what happens in an actual match is less important then build orders. Which invalidates about half of this post. Or maybe the whole post.”

It does not mean that at all. You can’t simply assert this, particularly because it bears no relation to how an RTS match plays out. If outside knowledge is all you need, we could all win the professional 1v1 league by devouring the team liquid wiki and watching replays. This has happened exactly 0 times in real life, Q.E.D you’re talking out of your arse.

This doesn’t even happen in turn based games, an instructive example is Chess. Chess has not only a stratification of players by skill levels, but is also Solved and a machine can beat a grand master.

“Why do I need to improve? Why would people spend almost as much time going over replays? Because RTS is about improving. Improving represent ability to score higher score or win more matches. Therefore RTS is about winning more matches. Not about playing matches, but winning matches. That is why players eschew 50% of game time (The point of the game.) for an elusive chance of higher win ration. (Which never going to materialize, because 50-50.) In other words, eschew low pleasure for middle pleasure in order to gain high pleasure.”

This is projecting. Which people, what players?

As to the why you would need to improve: there is not particular reason. All Wayward has to demonstrate is that RTS multiplayer is cool and fosters a mindset he thinks is good. If you disagree with that notion there isn’t much reason to ask why you would want to improve yourself when playing RTS multiplayer. You can safely just not play RTS. There is no need to accuse RTS players of a fear of defeat. I am unsure what you even expect, that players should play to lose? If you aren’t trying to win you aren’t playing the game, how can someone win but not play?

“Yeah, but that is not the nature of RTS, that is nature of contest. Contest itself does nothing to foster self-analysis. It is your decision to win more, lose less that drives you to self-analyse a situation. It is your own decision. RTS is simply a form of contest.”

Amazing, you summed up Wayward’s article, except he’s wrong, or something?

“Now we are geting to some kind of zen psylosophy. “Enjoy what you do.” The problem is, in that case, the doing is not enjoyable. If it was, then you would “Do what you enjoy.” This kind of mindset is employed by people who want to do something uncomfortable. Something they want to overcome. Does that mean RTS is uncomfortable and something to overcome? Pretty much.”

Sure, if you ignore what was written and make up what he said, in such a way as to pass some test you pull out of nowhere. When you put it that way, RTS really is uncomfortable.

“If you talk about focus on victory, then it means victory is the most enjoyable part of a match. So the match itself is not enjoyable. To the point of players ‘throwing’ tens or dozens of matches so the only thing they can experience is joy of victory. ”

Good thing the quoted section talks about not focusing on victory.

“RTS ceased to be a game, I.E enjoyable way to spend past time and become something else. Comparison to life is entirely fitting. Just as humans want to escape the harsh reality of life by watching movies, reading books and playing games, so do want to RTS players escape the harsh reality of RTS by claiming it is about improvement, learning and positive attitude towards loses.”

*rips bong* So deep, man.

“The problem is that outside of 25% of RTS players, noone can understand it. It is like hack and slash. It is great, untill you realize you beat monsters to beat monsters. It is nothing to nothing. Unless you like the activity. RTS is the same.”

So you will only find the activity worth doing if you like doing it? Sounds about right, but this is somehow a problem? What do you even want?

“Why would I do it. Insted of playing RTS, I can go to school and earn a degree. It is the same thing. Except it means something. Now, playing LoL is of course equaly meanigless, the difference is, LoL brings a good feeling of fun and joy. RTS brings sweat and stress and sorrow. Call it competive, inteligent, hard core, hard, it does not matter.”

So we get to the heart of things. You like MOBAs more. Whatever, dude. Have fun with that. But don’t for a second think your arguments against RTS can’t be turned back around at MOBAs. Not everyone likes MOBAs. I’m sure you’ve seen examples of it. Toxic Community! etc. Yet plenty of people take up, play and enjoy MOBAs on a regular basis.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The people who knowingly pick RTS want that type of demanding contest, with both a strategic and execution element. These people want to prove that they can improve or be able to best others. Regular life might not provide a battleground for them to compete and fufill this desire, even if is a harsh game.

LikeLike

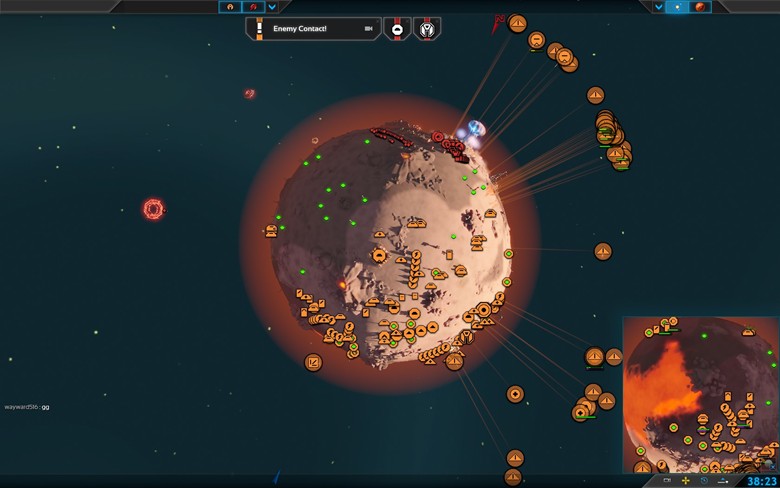

please tell me the game the pictures came from (beside CC)..i’ve been out of RTS for yrs. -bk

LikeLike